UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTABILITY OFFICE (US GAO)

Why GAO Did This Study

Since 1987, several countries have changed the management and funding of ATC services. Over the past two decades, U.S. aviation stakeholders, including an administration and Congress, have debated whether the FAA should continue to operate and modernize the country’s ATC system or whether an independent, self-financed organization—either public or private—should take on this role. In 2014, GAO found (1) that many aviation stakeholders saw challenges with aspects of the current U.S. system including funding instability and slow progress implementing capital improvements and (2) that most stakeholders agreed that separating ATC operations from FAA was an option. GAO was asked to explore issues that would be associated with such a change.

This report addresses (1) views of selected experts, aviation stakeholders, and the FAA on key transition issues and (2) lessons that can be learned from the transition experiences of selected countries.

GAO reviewed literature including previous GAO reports; worked with the National Academy to judgmentally select 32 experts from academia, think tanks, finance, the transportation industry and other related backgrounds, and interviewed and surveyed them; judgmentally selected and interviewed 20 aviation industry stakeholders to obtain a range of perspectives; and spoke with FAA. GAO reviewed documents related to U.K.’s, Canada’s, and New Zealand’s ATC transitions and interviewed current and former officials and stakeholders involved in those transitions.

What GAO Found

Experts, aviation stakeholders, and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) officials GAO spoke to said that if Congress decides to remove air traffic control (ATC) from the FAA, many issues should be considered. Key issues identified, consistent with GAO’s past work, relate to: (1) organizational management, (2) funding and financing, and (3) transition time and related costs.

First, organizational issues include defining roles, responsibilities, coordination, and ensuring workforce protections. Addressing these issues would affect the potential for success both of the ATC entity and of activities remaining with FAA, including safety oversight. For example, experts indicated that it would be key to morale to maintain existing employee benefits for both employees who remained at FAA and those who moved to a new ATC entity. Second, funding approaches for an ATC entity would depend, in part, on the type of organizational structure chosen, (e.g., public or private ownership), but most experts indicated a user-fee system should be implemented if a change occurred. Experts and aviation stakeholders raised issues associated with a user fee, including how to determine the level of fees and the impact of those fees on certain users, such as general aviation and cargo carriers. Both experts and stakeholders noted that the valuation ATC assets as well as the transfer of and, payment for, ATC assets will also need to be considered as well as responsibility for, and funding of pension and other liabilities. Third, experts estimated that it would take a number of years to appropriately develop legislation, as well as to negotiate, plan, and implement a transition and noted that there would be associated legal, financial, and other costs for such a transition.

GAO identified lessons learned from international experiences including the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, and New Zealand in restructuring their ATC services. Lessons include how these countries mitigated challenges associated with:

- ensuring coordination and collaboration between the ATC entity and the safety regulator—the New Zealand ATC entity put both formal and informal arrangements in place to ensure strong collaboration between the ATC entity and the regulator when developing new technologies.

- developing a funding and financing structure—the U.K. and Canada both learned that building in mechanisms to help mitigate financial risks is a key lesson that should be considered during the creation of a user fee system. Specifically, due to the decline in air traffic after September 11, 2001, the U.K.’s ATC entity had to work with the government to refinance and restructure the system, including finding a new investor and relaxing caps on user fees, so the U.K. ATC’s could raise fees.

- establishing an appropriate amount of time to plan and implement a transition—according to a consultant’s work on international civil aviation authority’s transitions for six countries, it took up to 7 years to complete a transition from government authority to a new entity.

Background

U. S. National Air Space and Its Users

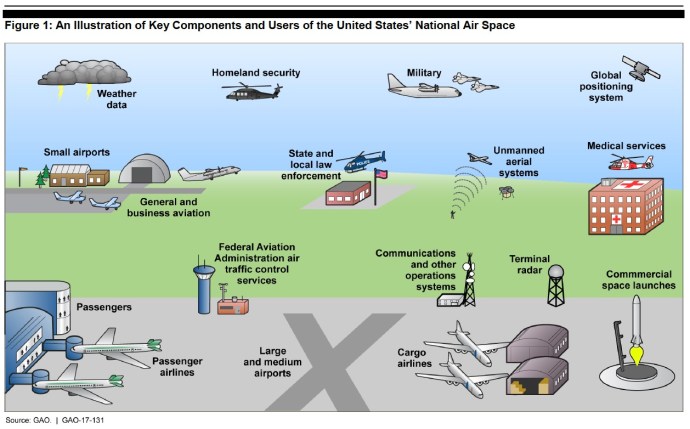

The FAA operates and maintains the U.S. national airspace system (NAS) which includes what is generally considered not only the busiest—handling over 50,000 flights per day—more than 700 million passengers each year—and the most complex air traffic control system in the world, but also the safest. In addition to commercial aviation and its passengers, other users—such as, airports, general, business, and public-use aviation (e.g., government users like DOD, Department of Homeland Security, law enforcement and border patrol), as well new entrants such as commercial space companies and unmanned aerial systems (UAS) also known as drones—have access to the national airspace. (See fig. 1).

FAA Funding Structure

Congress appropriates funding from the Airport and Airway Trust Fund (Trust Fund) as well as general revenues.9 Trust Fund revenues come from a set of excise taxes paid by users of the national airspace system, such as taxes levied on passenger tickets and commercial fuel. These funds support air traffic operations, facilities and equipment, research engineering and development, and grants in aid for airports. For example, in fiscal year 2015 FAA’s funding was over $15 billion; $14.6 billion came from Trust Fund Revenue.

FAA’s ATC Assets, Staff, and Employee-Related Financial Obligations

- Assets: FAA is responsible for operating and maintaining the air traffic control and supporting system and infrastructure, which includes air traffic control centers and towers, ground-based surveillance radars, communication equipment, automation systems, and facilities that house and support these systems. We reported in 2013 that this infrastructure totaled 66,570 facilities, systems, and unstaffed infrastructure assets and that the data on how FAA determines the condition of these facilities could be improved.

- Workforce: In fiscal year 2015, FAA had a workforce of about 40,000 employees including approximately 14,500 air traffic controllers, 5,000 air traffic supervisors and managers, 7,800 engineers and maintenance technicians, and over 7,000 FAA safety staff. FAA employees are represented by various labor unions including the National Air Traffic Controllers Association—the labor union representing FAA’s air traffic controllers—and the Professional Aviation Safety Specialists and American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, which represent FAA inspectors and FAA employees who maintain air traffic control equipment. FAA controllers and technicians are entitled to engage in collective bargaining, but prohibited by federal statute from participating in a strike. In addition, under federal statute, it is an unfair labor practice for a labor organization to call or participate in a strike or work stoppage, or slowdown or picketing if such picketing interferes with an agency’s operations.

- Pensions and other retirement benefits: Pensions for civilian federal employees generally are provided through two programs, the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS) or the Federal Employee Retirement System (FERS), depending upon when the employees were hired. Generally, employees hired before 1984 are covered by CSRS, while employees hired in or after 1984 are covered by FERS. Retiree health insurance benefits and retiree life insurance benefits for civilian federal employees generally are available through the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP) and the Federal Employees Life Insurance Program (FEGLI), respectively. All of these retirement programs require actuarial estimates to determine annual costs and accrued liabilities. The Office of Personnel Management (OPM) actuaries determine these costs and liabilities. According to FAA, the agency recognizes the cost of pensions and other retirement benefits during an employee’s active years of service. OPM recognizes the federal government’s liability for these benefits and pays such benefits after someone retires. However, OPM does not calculate the liability related to a particular agency. Consequently, FAA does not know what the amount is of its unfunded liability, if any, associated with employee retirement plans and does not report plan assets, accrued liabilities, or unfunded liabilities applicable to its employees and retirees.

About the United States Government Accountability Office

www.gao.gov

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) is an independent, nonpartisan agency that works for Congress. Often called the “congressional watchdog,” GAO investigates how the federal government spends taxpayer dollars.